The powerful underwater eruption of Tonga's Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai volcano earlier this year produced a plume that soared higher into Earth's atmosphere than any other on record, according to experts.

Researchers say the plume reached about 57 kilometres into the sky, extending more than halfway to space.

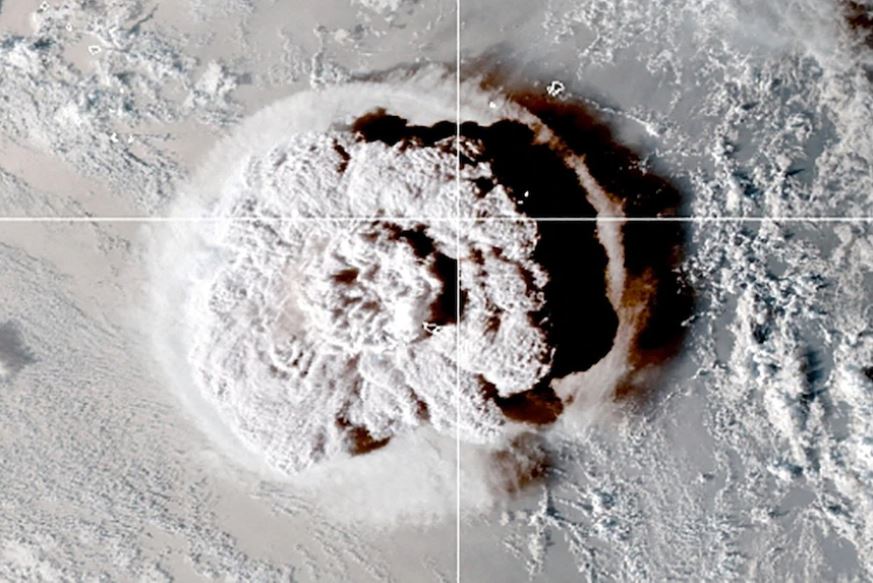

The white-grayish plume unleashed by the eruption became the first one documented to have penetrated a frigid layer of the atmosphere called the mesosphere, according to scientists who used multiple satellite images to measure its height.

Its plume was composed primarily of water, with some ash and sulphur dioxide mixed in, said atmospheric scientist Simon Proud, lead author of the research published in the journal Science.

Eruptions from land-based volcanoes tend to have more ash and sulphur dioxide and less water.

The deafening eruption on January 15 sent tsunami waves across the Pacific Ocean and produced an atmospheric wave that travelled several times around the world.

[caption id="attachment_29868" align="alignnone" width="873"] The January volcano eruption triggered a tsunami warning for several South Pacific island nations.(Reuters: NOAA/CIRA/Handout)[/caption]

The January volcano eruption triggered a tsunami warning for several South Pacific island nations.(Reuters: NOAA/CIRA/Handout)[/caption]

"To me, what was impressive is how quickly the eruption happened. It went from nothing to a 57-km high cloud in just 30 minutes. I can't imagine what that must've been like to see from the ground," Mr Proud said.

"Something that fascinated me was the dome-like structure in the centre of the umbrella plume. I've never seen something like that before," added Oxford atmospheric scientist and study co-author Andrew Prata.

The damage from the eruption obliterated a small and uninhabited nearby island and resulted in the deaths of six locals.

Its plume extended through the bottom two layers of the atmosphere, the troposphere and stratosphere, and about 7km into the mesosphere. The top of the mesosphere is the coldest place in the atmosphere.

The plume was far from reaching the next atmospheric layer, the thermosphere, which starts at about 85 km above Earth's surface.

A delineation called the Karman line, about 100 km above Earth's surface, is generally considered the boundary with space.

Scientists used three geostationary weather satellites that obtained images every 10 minutes to measure the blast and relied upon what is called the parallax effect: determining something's position by viewing it along multiple lines of sight.

"For the parallax approach we use to work, you need multiple satellites in different locations — and it's only within the past decade or so that this has become possible on a global scale," Proud said.

Until now, the highest recorded volcanic plumes were from the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines, at 40 km, and the 1982 eruption of El Chichón in Mexico, at 31 km.

Volcanic eruptions in the past likely produced higher plumes but occurred before scientists were able to make such measurements.

Source: ABC News