In 2017, a group of geologists hit the headlines when they announced their discovery of Zealandia –Te Riu-a-Māui in the Māori language. A vast continent of 1.89 million sq miles (4.9 million sq km) it is around six times the size of Madagascar.

Though the world's encyclopaedias, maps and search engines had been adamant that there are just seven continents for some time, the team confidently informed the world that this was wrong.

There are eight after all – and the latest addition breaks all the records, as the smallest, thinnest, and youngest in the world.

The catch is that 94% of it is underwater, with just a handful of islands, such as New Zealand, thrusting out from its oceanic depths. It had been hiding in plain sight all along.

"This is an example of how something very obvious can take a while to uncover," says Andy Tulloch, a geologist at the New Zealand Crown Research Institute GNS Science, who was part of the team that discovered Zealandia.

But this is just the beginning. Four years on and the continent is as enigmatic as ever, its secrets jealously guarded beneath 6,560 ft (2km) of water. How was it formed? What used to live there? And how long has it been underwater?

A laborious discovery

In fact, Zealandia has always been difficult to study.

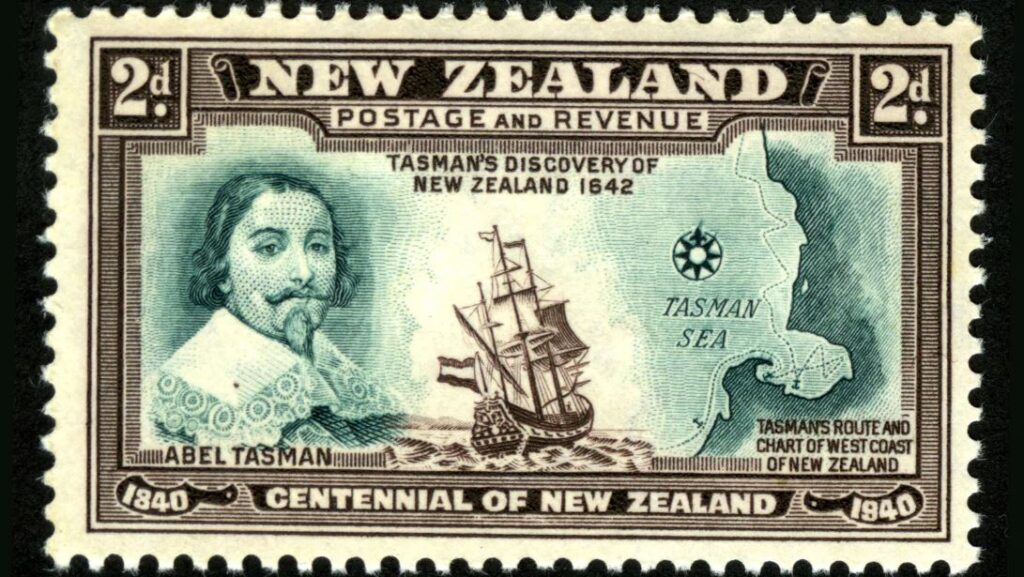

More than a century after Tasman discovered New Zealand in 1642, the British map-maker James Cook was sent on a scientific voyage to the southern hemisphere. His official instructions were to observe the passing of Venus between the Earth and the Sun, in order to calculate how far away the Sun is.

[caption id="attachment_28204" align="alignnone" width="906"] Possibly due to a quirk of geology, the enigmatic kiwi bird’s closest relative hails from Madagascar (Credit: Alamy)[/caption]

Possibly due to a quirk of geology, the enigmatic kiwi bird’s closest relative hails from Madagascar (Credit: Alamy)[/caption]

But he also carried with him a sealed envelope, which he was instructed to open when he had completed the first task. This contained a top-secret mission to discover the southern continent – which he arguably sailed straight over, before reaching New Zealand.

The first real clues of Zealandia's existence were gathered by the Scottish naturalist Sir James Hector, who attended a voyage to survey a series of islands off the southern coast of New Zealand in 1895.

After studying their geology, he concluded that New Zealand is "the remnant of a mountain-chain that formed the crest of a great continental area that stretched far to the south and east, and which is now submerged…".

Despite this early breakthrough, the knowledge of a possible Zealandia remained obscure, and very little happened until the 1960s. "Things happen pretty slowly in this field," says Nick Mortimer, a geologist at GNS Science who led the 2017 study.

Then in the 1960s, geologists finally agreed on a definition of what a continent is – broadly, a geological area with a high elevation, wide variety of rocks, and a thick crust.

It also has to be big. "You just can't be a tiny piece," says Mortimer. This gave geologists something to work with – if they could collect the evidence, they could prove that the eighth continent was real.

Still, the mission stalled – discovering a continent is tricky and expensive, and Mortimer points out that there was no urgency. Then in 1995, the American geophysicist Bruce Luyendyk again described the region as a continent and suggested calling it Zealandia. From there, Tulloch describes its discovery as an exponential curve.

[caption id="attachment_28205" align="alignnone" width="949"] Tasman’s ships left New Zealand after a bloody encounter with the Māori people – but he believed that he had found the legendary southern continent (Credit: Alamy)[/caption]

Tasman’s ships left New Zealand after a bloody encounter with the Māori people – but he believed that he had found the legendary southern continent (Credit: Alamy)[/caption]

With this technology, Zealandia is clearly visible as a misshapen mass almost as large as Australia.

When the continent was finally unveiled to the world, it unlocked one of the most sizeable maritime territories in the world. "It is kind of cool," says Mortimer, "If you think about it, every continent on the planet has different countries on it, [but] there are only three territories on Zealandia."

In addition to New Zealand, the continent encompasses the island of New Caledonia – a French colony famous for its dazzling lagoons – and the tiny Australian territories of Lord Howe Island and Ball's Pyramid. The latter was described by one 18th-Century explorer as appearing "not to be larger than a boat."

A mysterious stretching

Zealandia was originally part of the ancient supercontinent of Gondwana, which was formed about 550 million years ago and essentially lumped together all the land in the southern hemisphere. It occupied a corner on the eastern side, where it bordered several others, including half of West Antarctica and all of eastern Australia.

Then around 105 million years ago, "due to a process which we don't completely understand yet, Zealandia started to be pulled away", says Tulloch.

Continental crust is usually around 40km deep – significantly thicker than oceanic crust, which tends to be around 10km. As it was strained, Zealandia ended up being stretched so much that its crust now only extends 20km (12.4 miles) down. Eventually, the wafter-thin continent sank – though not quite to the level of normal oceanic crust – and disappeared under the sea.

Despite being thin and submerged, geologists know that Zealandia is a continent because of the kinds of rocks found there. Continental crust tends to be made up of igneous, metamorphic and sedimentary rocks – like granite, schist and limestone, while the ocean floor is usually just made of igneous ones such as basalt.

When the supercontinent of Gondwana broke up, fragments drifted all across the globe. Many of its ancient plants still live in the Australian Dorrigo forest (Credit: Getty Images)[/caption]

When the supercontinent of Gondwana broke up, fragments drifted all across the globe. Many of its ancient plants still live in the Australian Dorrigo forest (Credit: Getty Images)[/caption]

Abel Tasman arguably did find the great southern continent, though he didn’t realise 94% of it is underwater (Credit: Alamy)[/caption]

Abel Tasman arguably did find the great southern continent, though he didn’t realise 94% of it is underwater (Credit: Alamy)[/caption]

Satellite data can be used to visualise the continent of Zealandia, which appears as a pale blue upside-down triangle to the east of Australia (Credit: GNS Science)[/caption]

When the continent was finally unveiled to the world, it unlocked one of the

Satellite data can be used to visualise the continent of Zealandia, which appears as a pale blue upside-down triangle to the east of Australia (Credit: GNS Science)[/caption]

When the continent was finally unveiled to the world, it unlocked one of the