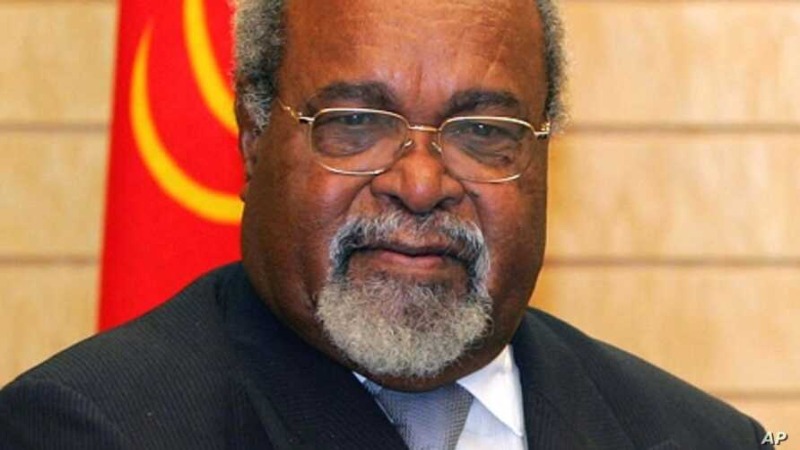

Charisma! Michael Thomas Somare had it by the canoe load.

Papua New Guinea’s Father of the Nation, the Grand Chief, who has just died of pancreatic cancer, has left an enduring legacy.

He lived to the age of 84 – an extraordinary innings in a country where the average life expectancy is 20 years short of that at 64.

But he achieved so much he could have been 104. In the general history of Papua New Guinea that I authored – last updated in the year 2000 and covering PNG’s first quarter-century of independence – Somare is mentioned on no fewer than 62 pages.

It simply reflects his dominance of the political scene in those years. I have a bank full of memories of Sir Michael and I am pleased to say that we became good friends.

Naturally, there was the odd disagreement or two. For example, he deported me in 1984! More on that later.

The first time we ever spoke I left a little ashamed.

It was very early in my time in Papua New Guinea.

I had arrived in PNG 1974, the year before independence, as a young journalist working on secondment from the ABC to the then newly created National Broadcasting Commission of PNG.

Somare was Chief Minister and the NBC News Editor sent me along to a Somare news conference.

At the time, there were five full-time Australian Foreign Correspondents in PNG and I was in awe of them as much as I was of Sir Michael.

I recorded the news conference but did not say a word.

At the end, Somare, who had been a broadcast journalist himself at Radio East Sepik, smiled at me and said, “Young man, what do you think news conferences are for? You can ask questions!”

In my subsequent career I must have asked him hundreds.

I also had the distinct pleasure in 1976 when I captained the Papua New Guinea Rugby League representative team, the Kumuls, of introducing Sir Michael to each of my fellow Kumuls just before the match we played against a visiting New South Wales Country side.

Somare first won a seat in the pre-independence House of Assembly of PNG in 1968.

He stood for the Pangu Party - the Papua and New Guinea United Party! PANGU had been formed the year before by Somare and other members of what they called the “bully beef club” at the Administrative College in Port Moresby.

He became Opposition Leader.

The Australian Minister responsible for Papua New Guinea at the time was Charles Edward Barnes who firmly believed that PNG was totally unprepared for independence and he predicted independence would not be achieved before the end of the 20th Century!

And he was in no mood to hurry things up.

Although Barnes held Australian ministerial responsibility for PNG for a crucial eight years it is instructive that the authoritative Encyclopaedia of Papua and New Guinea, published in 1972, devoted just six lines to Barnes – six lines in its three volumes covering 1231 pages.

Those six lines simply record that he was the Country Party Member for MacPherson in Queensland, that he became minister in 1963 and that his portfolio’s name was changed to External Territories in 1968.

Perhaps he should be given credit for inadvertently advancing the independence cause because he became an object of ridicule amongst young, politically aware Papua New Guineans like Michael Thomas Somare.

My wife, Pauline, who retains her PNG citizenship distinctly remembers Sir Michael’s response when he was once asked if PNG got its independence too early.

He said the country may not have been well prepared but he and those who supported him did it for their dignity and the dignity of their people.

Somare was a natural leader who resolutely believed in consensus and compromise.

In a country like PNG where the people speak at least 860 distinctly different languages his style of leadership, especially in the early years, was exactly what was required.

Putting together multi-party coalitions in PNG is no simple task.One of the international issues he had to deal with early on was how to handle PNG’s relationship with its giant next-door neighbour, Indonesia, especially since the indigenous people living in the western half of the main island of New Guinea are ethnically similar to his own people.

The Free West Papua cause has enormous sympathy in the rest of Melanesia and countries like Vanuatu - without the complication of PNG’s 850 km land border with Indonesia - can loudly espouse independence for West Papua.

Which brings us back to Somare deporting me.

It was 1984 and an Indonesian military sweep against the military wing of the Free West Papua movement, the OPM, led to 10,000 refugees fleeing across the border into PNG’s West Sepik Province.

I went to the border and reported extensively on this which prompted the ABCs Four Corners program to send a team up to do a story.

I put the reporter, Alan Hogan, in touch with contacts of mine along the border who arranged for Hogan to get an interview with the OPM Rebel Commander, James Nyaro.

When that went to air, PNG’s Secretary of Foreign Affairs was furious.

We were accused of either entering Indonesia illegally to obtain the interview or enticing an illegal immigrant to cross the border.

Somare was Prime Minister and I was ordered to leave.

We had two children and Pauline had to accept being thrown out of her own country to keep the family together.

I was allowed back in 1987 and then spent another 12 years as the ABCs PNG Correspondent during which time Somare awarded me an MBE.

I am feeling particularly sad for Sir Michael’s family.

I got to know his son, Arthur, reasonably well but I know his two daughters, Bertha and Dulciana, a little better and I know they would be grieving.

Pauline and I used to play social tennis with Bertha and one of Sir Michael’s speechwriters, Michael Ekin-Smyth.

While Dulciana spent some time working in the ABC office in Port Moresby as Radio Australia’s PNG journalist.

That was after I had completed my term there.

But we worked together when I was sent up to Port Moresby on a short-term relief assignment.

The Grand Chief served as PNG’s Prime Minister on three separate occasions.

He became a major statesman in the Pacific region and was hugely admired throughout the rest of the Pacific Islands.

But of all his achievements the one that impressed me the most was his gracious acceptance of defeat.

In 1980, five years after Somare led PNG to independence, Sir Julius Chan, his former Deputy Prime Minister, mounted a challenge and Sir Michael was defeated on the floor of Parliament in a Vote of No Confidence.

There were those around Sir Michael at the time who were urging him to declare a State Of Emergency and to hold on to the top job.

However, Somare told them he would abide by the Constitution he had done so much to put in place and he accepted going into Opposition.

That has set the standard for PNG ever since.

Despite the volatility of the country in so many other respects there have now been numerous peaceful changes of government.

Somebody like Donald Trump could have learnt a thing or two about being a gracious loser from the Grand Chief Michael Somare.

Long time ABC journo Sean Dorney on the passing of late Grand Chief Sir Michael Somare – Story taken from Facebook showing the region mourning