The contents of a sinister note found on John Edwards’ desk after he killed his children can be revealed for the first time and exposes a wider issue.

Metres from where John Edwards killed himself after murdering his two children, police found a post-it note on the desk in his study. Written on it was “Justice delayed is justice denied.”

Also on the desk were family law documents, with more discovered in folders in the same room. Court orders were stuffed in the driver’s door pocket of the retired financial planner’s golden Nissan Patrol 4WD.

Details about the chilling note and documents can be revealed for the first time and further highlight the serious risks to women and children in the family law system.

At the West Pennant Hills house where Jack and Jennifer lived with mother Olga, and where Edwards shot them dead, family law documents were found in a green suitcase in the lounge room. They were in piles, plastic sleeves, folders. They were on Jennifer’s school file.

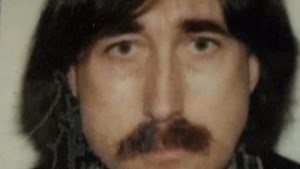

[caption id="attachment_8918" align="aligncenter" width="909"] John Edwards murdered his own children before killing himself. His wife, Olga, took her own life several months later. Picture: 60 MinutesSource:Channel 9[/caption]

John Edwards murdered his own children before killing himself. His wife, Olga, took her own life several months later. Picture: 60 MinutesSource:Channel 9[/caption]

The proceedings were at the forefront of Olga’s mind when a neighbour approached outside her house, shortly after she learned on the evening of July 5, 2018, that her children had been killed.

“I said, are you OK? What’s going on?” the neighbour told police. “She said, ‘My ex has come and killed my children. He has killed my children. Our court settlement day is in two weeks. This is so fucked up.’”

State coroner Teresa O’Sullivan said in April as she handed down her findings into the deaths of Jack, 15, and Jennifer, 13, that it was “impossible” to understand what happened in the Edwards family without understanding the family law proceedings that dominated their final years.

[caption id="attachment_8919" align="aligncenter" width="856"] John Edwards had a post-it note saying: ‘Justice delayed is justice denied’ Picture: 60 MinutesSource:Channel 9[/caption]

John Edwards had a post-it note saying: ‘Justice delayed is justice denied’ Picture: 60 MinutesSource:Channel 9[/caption]

The court case offered context to pivotal moments, Magistrate O’Sullivan said, such as Olga reporting to police that Edwards had physically abused the children a week after those same allegations had been treated dismissively in court. Officers misrecorded her complaint and took no further action.

Hayley Foster, the CEO of Women’s Safety NSW, told NCA NewsWire the Edwards case “shows all of the massive failings in the system”.

[caption id="attachment_8920" align="aligncenter" width="969"] The coroner said it was ‘impossible’ to understand what happened in the Edwards family without understanding the family law proceedings. Picture: 60 MinutesSource:Channel 9[/caption]

The coroner said it was ‘impossible’ to understand what happened in the Edwards family without understanding the family law proceedings. Picture: 60 MinutesSource:Channel 9[/caption]

“But they are not one off incidents,” she said. “They are not rare occasions. The sort of failings we saw in this case are failings we see every day.”

Ms Foster said significant moments in family law proceedings are, like the time of separation, a dangerous time in which the risk of violence is heightened.

She said much of the behaviour displayed by Edwards after the separation, including the note on his desk and a reference to “my abducted children” in an email, was typical of perpetrators who end up in the family court system.

“Most people using violence and abuse in relationships actually identify as the victim, as the aggrieved,” Ms Foster said.

Usually there is a strict prohibition on the reporting of family law proceedings to protect people’s privacy. But in the unique and tragic circumstances of Jack and Jennifer’s homicides and Edwards and Olga’s suicides, this was significantly lifted at the inquest.

When Olga filed the proceedings in April 2016, she attached an affidavit saying the kids did not want to see John and disclosed numerous instances of violence, including him hitting Jack under the eye with a book and pinning him up against a wall in Paris. She wrote that she feared “one day I would come home and find my child dead”.

A family consultant report in the case, dated September 2016, said “While the children may have some valid reasons for being upset with their father, their complete rejection of a relationship with him seems extreme and could lead to emotional difficulties in later life if they are not provided the opportunity to attempt to repair the relationship”. It also noted the children’s views may be tied to Olga’s feelings.

[caption id="attachment_8921" align="aligncenter" width="943"] Olga reported John Edwards to police. Picture: 60 MinutesSource:Channel 9[/caption]

Olga reported John Edwards to police. Picture: 60 MinutesSource:Channel 9[/caption]

In December 2016 the children were ordered to spend three hours with their father every Saturday following a court hearing at which Magistrate O’Sullivan found independent children’s lawyer Debbie Morton misled the court by underplaying Edwards’s history of violence as “heavy-handed parenting”.

In May 2017, Ms Morton wrote to Olga’s lawyer that if she continued to be “uncooperative” in getting the kids to therapy with their father, she would be left with “no other alternative” but to recommend Jack and Jennifer be placed in Edwards’ care.

[caption id="attachment_8922" align="alignnone" width="957"] Olga and John Edwards.Source:News Regional Media[/caption]

Olga and John Edwards.Source:News Regional Media[/caption]

At a hearing in June 2017, Judge Geoffrey Monahan expressed frustration the Saturday hours were not being adhered to. He said he had not seen anything to suggest Jack and Jennifer, then 14 and 12, should not see John other than they “don’t want to go” and said of Olga: “I think mum can try a bit harder, frankly”.

Ms Foster said the family law system prioritises contact over risk.

“If the person using violence or abuse is getting messages somewhere in the system that they are aggrieved and they should be able to expect more, that can enliven him. It can make him feel more entitled to continue to pursue his rage,” she said.

“If he is starting to get stopped in the system … there can be a backlash effect.”

In February 2018, a judge granted sole custody to Olga, noting it was up to the children whether or not they continued to see their father. They did not want to.

Around this time, a family friend told police, Edwards “started to become more serene” and “seemed like he was moving on with things”.

“He started to talk about things other than Olga, he didn’t seem to need to debrief about what was happening with her,” the friend said in her witness statement.

It was also around this time, Magistrate O’Sullivan found, that Edwards decided to kill Jack and Jennifer.

The coroner found the deaths were preventable, occurring after a litany of individual, systemic and regulatory failures. She made a number of recommendations to improve information sharing between the family law courts, NSW Police and the gun registry.

[caption id="attachment_8923" align="alignnone" width="834"] Jack and Jennifer Edwards did not want to see their abusive father.Source:AAP[/caption]

Jack and Jennifer Edwards did not want to see their abusive father.Source:AAP[/caption]

Ms Foster said such changes were a “no-brainer” and called for them to extend to state and territory magistrates as well as specialist domestic violence services working with women on the front lines.

She said a new initiative requiring judges to undergo family violence training was positive but lawyers, report writers, and all involved should be specially trained in things like perpetrator behaviour and the impact of violence and abuse.

[caption id="attachment_8924" align="aligncenter" width="1141"] The Edwards family. Picture: 60 MinutesSource:Channel 9[/caption]

The Edwards family. Picture: 60 MinutesSource:Channel 9[/caption]

“When we have actors in the system that don’t have that understanding, or that hold problematic or archaic views around gender roles and expectations, then we have a very dangerous situation where the abuser can be given dangerous signals about the course of entitlement they are proceeding with,” Ms Foster said.

“In this case, everything went wrong, and it did result in a homicide. There are many factors why someone might escalate to homicide or not.

“But the reality is many, many, many women currently are unprotected in situations where there is that serious risk. And they can’t at the moment consistently rely upon police and the courts to keep them safe.”

SOURCE: News.com.au